Measuring Binary Star Properties

Multiplicity affects a planetary system's environment. For example, close multiplicity (separations less than 50 AU) reduces the planet occurrence rate in Kepler planets by a factor of 3, but the physical process causing this effect is not known. One complicating factor in understanding the mechanisms governing planet survival in binary stars is difficulty accurately characterizing the components of close binary stars. Although small numbers planet-hosting binary systems have been analyzed in detail, a more efficient methodology is necessary for developing a statistically robust sample of planet-hosting binaries with accurate properties.

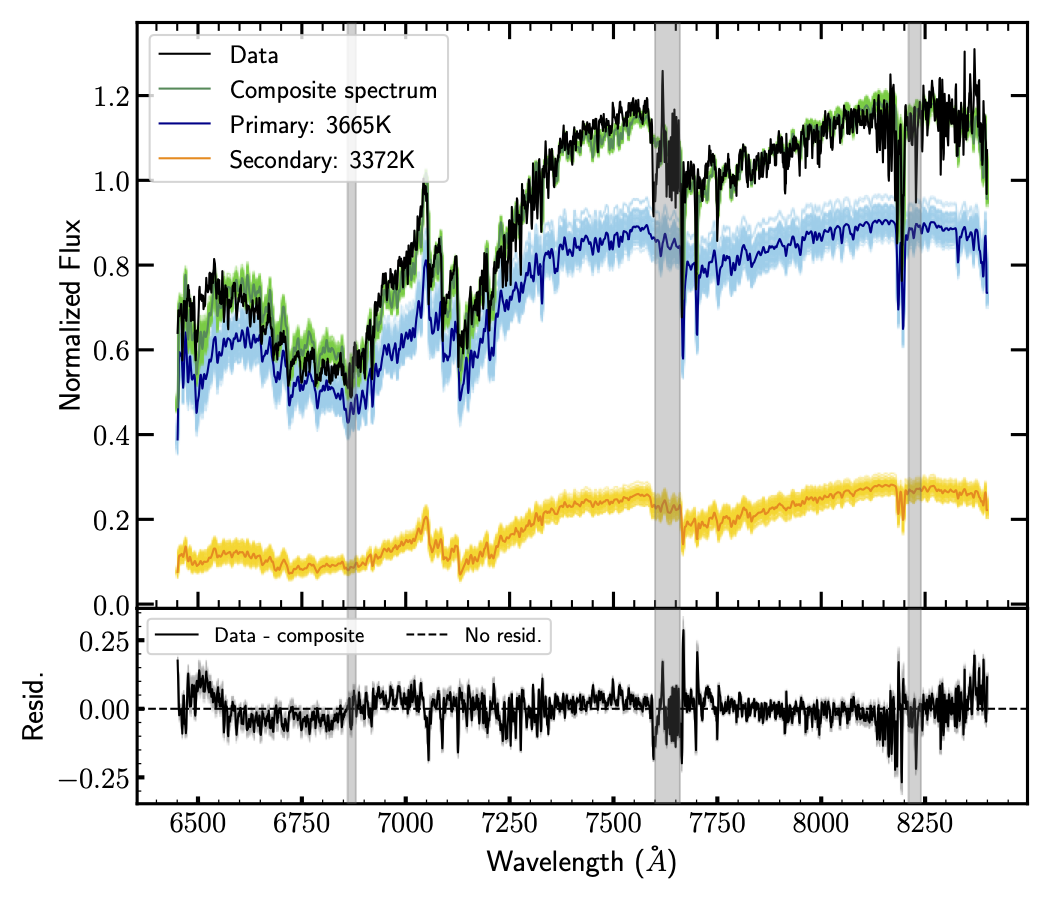

I developed a technique to retrieve the properties of spectroscopically-unresolved binary stars and am applying it to a variety of samples of planet-hosting binary stars from the Kepler mission. I began by analyzing archival data (Sullivan, Kraus, and Mann 2022), and have ongoing observational programs at the Hobby-Eberly Telescope at McDonald Observatory to collect data on a larger sample of Kepler binary star planet hosts. As a first scientific step, I published a paper that found that most supposed super-Earths in binaries are actually sub-Neptunes (Sullivan and Kraus 2022b).

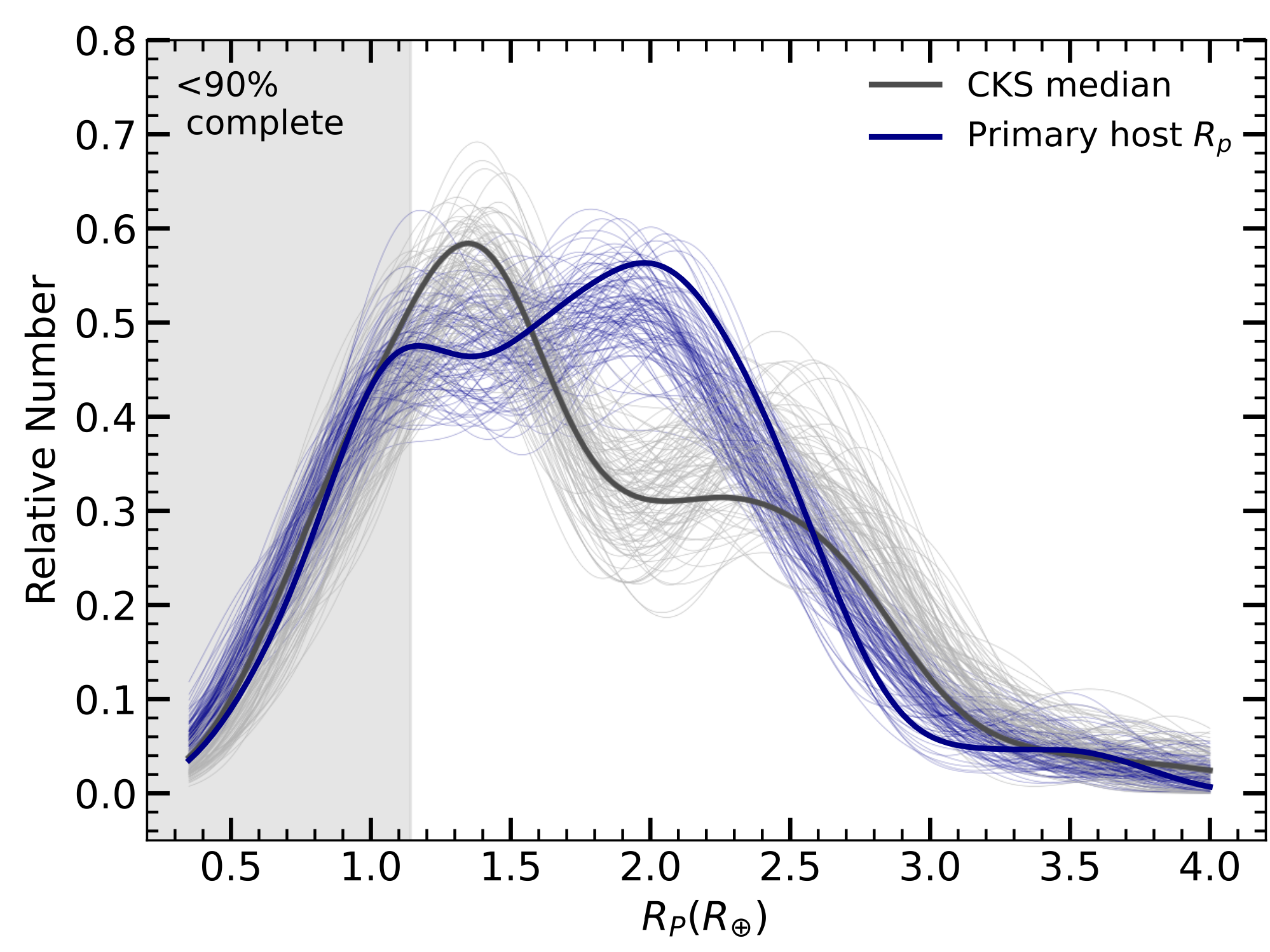

Next, we explored the population of small planets in or near the radius gap and in binary stars, where we did not detect the radius gap in a population of 120 small planets. We suggested that this is the result of the radius gap potentially having a separation-dependent location because of the impact of the secondary star on planet formation and evolution (Sullivan et al. 2023). Recently, we followed up this effort with a larger sample and found that the sub-Neptune population of planets is suppressed in close binaries, suggesting that binaries are indeed inhibiting large plaent formation (Sullivan et al. 2024).